Children Whose Behaviour Harms Others

Scope of this chapter

This brief chapter in our procedure’s manual is here to underline our child-first approach to responding when a child exhibits harmful behaviours. A ‘Child First’ approach underlines that “children should be seen as children, and it is the responsibility of adults to overcome the structural barriers that are preventing the children from achieving their potential, it is the role of adults to meet the needs of the children1".

The Children Acts of 1989 and 2004, along with the Children and Social Work Act of 2017, provide a legal framework that emphasises the welfare of the child as the paramount concern for professionals considering how best to intervene in family life. These principles apply to all children. This policy has been created for all practitioners who may work with children who have harmed other children. We have highlighted what constitutes harm within the body of the document. We have reviewed local and national guidelines and included some references & hyperlinks to the relevant evidence base for children who harm. We have also provided links and contact details to the wider multi-agency services who specialise in children who have harmed.

When working with children who have harmed, there are numerous complexities which need consideration such as the potential of a child requiring a child-in-need assessment and subsequent support plan, similarly the potential need for child protection planning and the possibility of them being subject criminal justice process. These particular factors warrant use of Lincolnshire's ‘Child First’ approach.

[1] Youth Justice Board, 2024, ‘Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool’, YJB Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool

Amendment

This chapter was refreshed in April 2025.

Harmful behaviour is a spectrum of undesirable, inappropriate and concerning behaviours which create alarm or distress in another person or cause actual physical or sexual harm. It can include physical, sexual or emotional abuse, exploitation, bullying, technology assisted harm, coercive control and may be interfamilial.

Adhering to child protection procedures is crucial when working with a child whose behaviour has harmed others or a child who has been harmed by another child. Following the nationally established ‘Working Together’ safeguarding guidelines will ensure that all children receive appropriate interventions. The complexity in this scenario is developing assessments and interventions that can support a child that has experienced harm whilst also addressing the harmful behaviour of another child. Any plan must seek to reduce the concern for others whilst also considering everyone’s personal safety and wellbeing.

Lincolnshire Children’s Services, Lincolnshire’s Integrated Care Board, Health Teams and Lincolnshire Police must work collaboratively, involving Education and other partners to implement these procedures effectively. When working with a child whose behaviour may have harmed another, professionals must strive to see the ‘whole child’ and to keep them in focus throughout any assessment or intervention. Harmful behaviour exhibited by a child should be understood as outside of healthy child development, this could be a potential indicator that a child is experiencing neglect or abuse themselves. As such, professionals should prioritise professional curiosity, striving to understand the child’s lived experience, and the underlying functionality of their behaviour.

To this end, where concerns are identified, referrals to children’s social care must be submitted for both the child who caused/ is causing the harm and the child who experienced/ is experiencing the harm.

When considering the harm to others from a child’s behaviour, please note the procedural definition of serious impact is identified as: {the behaviour} can have a detrimental impact for others (members of the public, family members, potential known or unknown victims) and the recovery is likely to take time or in some circumstances not be possible. Recovery is considered the point where the person can return to everyday functioning as it was before the event or behaviour. The impact can be physical or psychological”1. This would include where there are allegations of serious sexual or violent offences.

When services become aware of harmful behaviour and professionals are aware of a context or further information which indicates the child is likely to be experiencing significant/serious harm themselves, a Strategy Meeting must be convened.

Where the impact of a child’s harmful behaviour on others could be serious, consideration must be given to a Strategy Meeting being held. Full consideration should be given to a child’s severe and profound difficulties and any presenting behaviour. If a decision is taken that no Strategy Meeting is to be held, the rationale for this must be clearly recorded on the child’s record by the Practice Supervisor/manager in children’s social care.

Where a Strategy discussion is convened for these circumstances, Education partners should always be invited. Where the child whose behaviour has caused the harm is aged 10 or over Future4Me (youth justice services) should be invited.

Any strategy meeting/discussion must explore the ‘whole picture’ for all the children involved/impacted. Where concerns are raised within a strategy discussion regarding a child who is not the subject of that specific meeting, the Children’s Services Practice Supervisor leading the strategy meeting must give consideration to the safety of that child and if additional Child Protection activity in relation to that child is required.

MOSAIC relationships should be created to reflect the dynamics between the children. ‘Other/ Friend’ and ‘Alleged abuser’, are available options to distinguish relationships. Adopting this practice will support professionals, such as the Emergency Duty Team, to prioritise the safety of all involved children.

In taking a collaborative, multi-agency approach to a convening strategy meeting and developing a collaborative child protection strategy we are best equipped to ensure that:

- children who have caused harm receive the support they need to prevent further harm (to themselves and others)

- anyone who has been harmed has their needs separately assessed and their safety prioritised.

The guidance on strategy discussions is available at: Strategy Discussions.

[1] Youth Justice Board, 2024, ‘Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool’, YJB Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool

Seeing the ‘whole child’ requires us to frame our observations within a developmental perspective. Research has shown that children from an early age can tell the difference between things that are inherently wrong and things that people say are wrong. This means that even young children have their own sense of what is fair and just, not just what adults tell them. Reflecting on this knowledge of children’s moral development is important because it should lead us to explore how the child in our focus has learned about right and wrong. When a child’s behaviour causes harm to another, they do not as a result deserve less of our focus or support. The harm resulting from their behaviour should not eclipse their needs as a child. We should, as child centred practitioners, want to know what the behaviour is telling us about the child’s context and the child’s own experience of justice and fairness. We should want to explore what they have witnessed, experienced or watched that might be shaping their understanding of morality and justice. We know that children developing in an environment free from abuse and violence do have a basic idea of what is moral and can separate what they believe from what they learn from their environment. Within the context of preventing further harm, we need to commit to exploring the child’s world and offering intervention that can prevent further harm to the child or to others2.

[2] Ha Na Yoo, Judith G. Smetana, Children’s moral judgments about psychological harm: Links among harm salience, victims’ vulnerability, and child sympathy; Journal of Experimental Child Psychology,

Volume 188, 2019, 104655; ISSN 0022-0965, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.06.008.

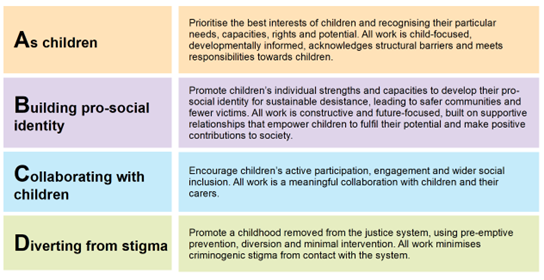

The four ‘tenets’ of Child First provide a framework for working with children:

3

3

In Lincolnshire we adopt a trauma informed approach. We need all practitioners to have as their key stance, an elevated level of professional curiosity into the factors that have impacted the child’s development leading to the harmful act/s. Every effort should be made to enable children to engage, and participate in, assessment and interventions.

[3] Youth Justice Board, 2024, ‘ Child First Toolkit’, Final-Child-First-Toolkit-Guidance-Document-.pdf (yjresourcehub.uk)

When planning an assessment/intervention the discussion between practitioner and line manager should always address:

- How can we support a child who has harmed another to reduce concerns and ensure they are not experiencing harm themselves? What threshold of intervention are we considering? Who else needs to be involved?

- How can we explore the concerns safely with the child and their family?

- Are there concerns for staff safety or the safety of others that need consideration?

- What format should we use for sessions?

- What is the safest location for work to take place?

- Who else do we need to work with to assess the needs and develop a shared plan?

- What strengths can be built on to mitigate concerns?

- What barriers are preventing this child from reaching their full potential?

- How can we support this child to reach their full potential?

- What is the child’s voice telling us about their lived experience? How can we help them share their experience from their perspective?

- What behaviour has caused this child to be referred?

- Who has been harmed? How is their safety being assessed and promoted?

- What does the child say about the behaviour?

- What do the parents/ carers say about the behaviour?

- What is this child’s behaviour telling me about their lived experience?

- Who else do I need to speak to, to understand this child’s lived experience?

- What do other agency assessments and records tell me about this child and how is this relevant to my assessment?

- What significant events (positive or negative) have happened in this child’s lifetime? How do these map out against a timeline of harmful behaviours?

- What, if any, previous harmful behaviours have been recorded/ shared with me? Are the current concerns an increase in frequency or severity? What triggers or patterns to behaviours have I observed?

An assessment should always conclude with an analysed and reflected upon professional position statement. This should set out the hypothesis of why the behaviour happened, what evidence supports this view, if others hold differing opinions, and make recommendations as to how future harm (to the child and/ or others) can be minimised. In addressing future concerns always set out:

- Who might be harmed?

- How might they be harmed?

- When the harm is likely to occur?

- In what context/ circumstance might future concerns arise?

- What does a good safety plan look like?

- What do future contingencies need to include?

Practitioners must create case records which include: The child’s history, current details including family networks, both the details and the outcomes from assessments and interventions, together with any professional reflections from involved practitioners. Each agency involved should create individual records for each child. Where harm is caused by one child to other children their records should indicate this, and it should be easy to identify the relationships, and the impact behaviour has had on each child and their family.

All information and analyses from each agency should be requested, shared and recorded so that there can be a true partnership approach to seeing and supporting the ‘whole child.’ Access to information from all partner’s is essential to making the right decisions when managing potential future concerns and making decisions about closure to services. Ensuring all information is appropriately recorded and linked to the relevant children is important. Not only because it supports current decision making and step in - step out planning, but because access to accurate records will improve responses to future referrals. Having access to a well evidenced clear analysis will make it more straight forward for colleagues coming new to the child to make an informed decision about when further work might be needed.

In feedback from children, they have consistently stated that they do not like repeating their story and so it is important that as much information as possible is gained from a range of sources before meeting the child and their family to complete any assessment1. They have also told us they want professionals to be honest and to be clear what is going to happen to information they share. They want to know what they can control and whether they have any say in which adults have access to their information. Children are clear that they understand what ‘need to know’ means and they value time taken to help them understand the who and why. Children also like to know about what happens to records over time and how they can access information when workers are no longer involved.

[1] Youth Justice Board, 2024, ‘Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool’, YJB Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool

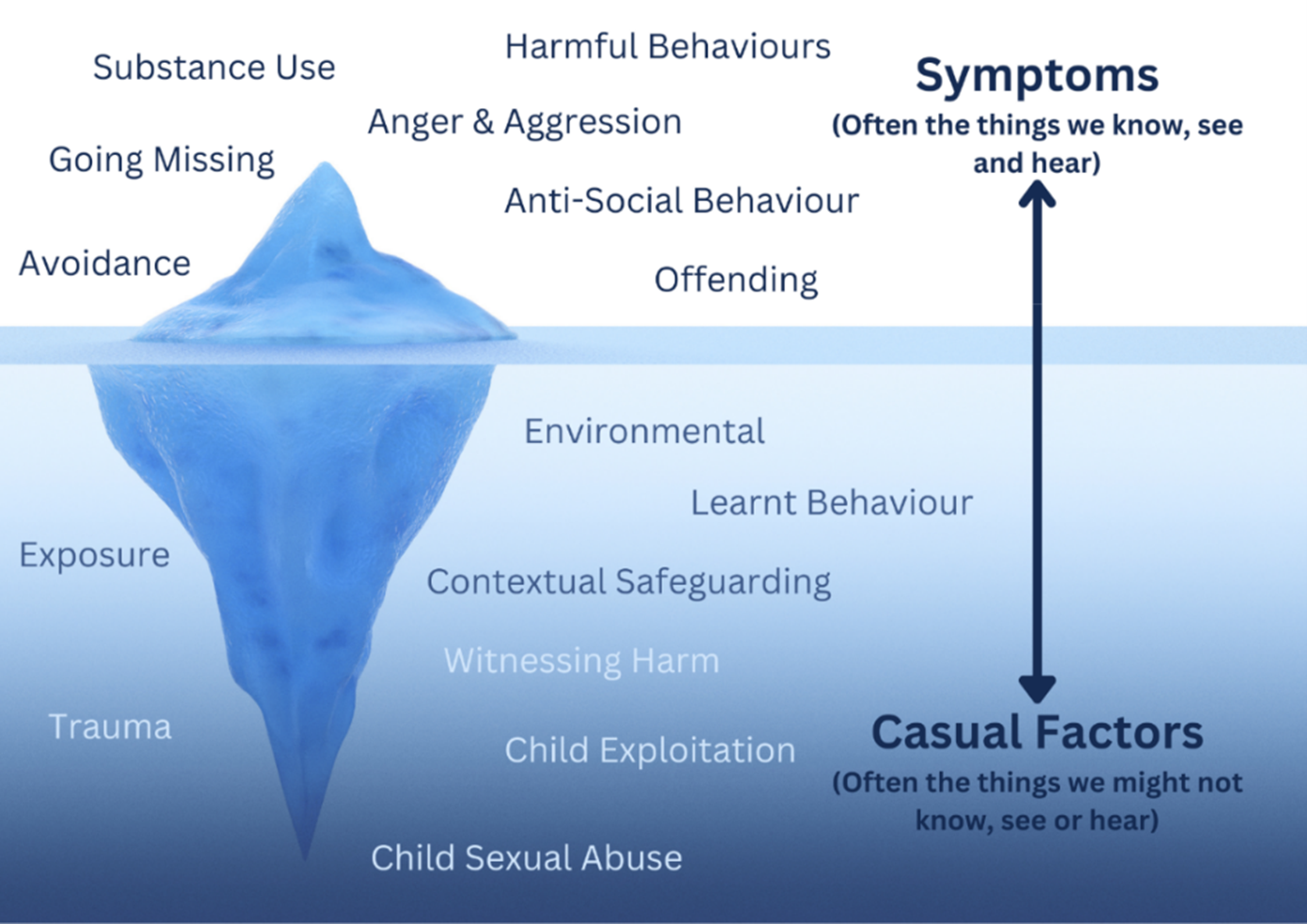

The Lincolnshire Safeguarding Childrens Partnership has written a ‘Professional Curiosity Resource’ to support practitioners.

This is a useful aid to practice reflection that helps practitioners consider what factors may be underlying the surface level behaviour we see from children. It demonstrates the need to look beneath the presenting behaviours to understand what is happening for a child and why this may be happening.

[1] Youth Justice Board, 2024, ‘Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool’, YJB Prevention & Diversion Assessment Tool

In Lincolnshire there is a small, dedicated team of Child & Adolescent Mental Health Harmful Behaviour Specialists whose role objective is to support and respond to the needs of the child cohort who present with sexually concerning behaviours. This team sits within the wider Complex Needs Service working between CAMHS and the Local Authority.

A specific procedure for working with Children and young people who display sexually inappropriate or harmful behaviours can be found here. Child on Child Sexual Harassment, Sexual Abuse and Sexually Harmful Behaviours Procedure.

Last Updated: April 22, 2025

v33